Back to Blog

1.1 The

Web3 SecuritySolidityAuditDeFi

Smart Contract Proxy Patterns: Security Guide 2026

The Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) architecture was fundamentally predicated on the principle of immutability: once a bytecode is deployed to a specific address, its logic remains unalterable. This characteristic, while essential for censorship resistance and trustlessness, presents significant operational friction for iterative software development. Inevitable bug discovery, evolving business logic, and gas optimization requirements have necessitated the adoption of "Upgradeability Patterns."

As of 2026, smart contract upgradeability has transitioned from an optional feature to critical infrastructure—and, paradoxically, one of the most severe attack vectors in the decentralized ecosystem. Recent academic literature, specifically the seminal study "The Dark Side of Upgrades" (2025) and data from automated analysis engines PROXION and CRUSH, indicates that the complexity of these mechanisms often obscures systemic risks. Current telemetry shows that over 54.2% of active Ethereum contracts utilize some form of call delegation, governing billions in Total Value Locked (TVL).

This report provides an exhaustive technical analysis of the four dominant upgradeability patterns: Transparent Proxy, UUPS (Universal Upgradeable Proxy Standard), Beacon Proxy, and the Diamond Standard (EIP-2535). We dissect the low-level EVM mechanics, storage layout management, and security implications identified in recent high-profile exploits.

1. EVM architectural foundations for upgradeability

Understanding the security of upgradeability patterns requires a granular dissection of the primitives that enable the separation of logic and state.

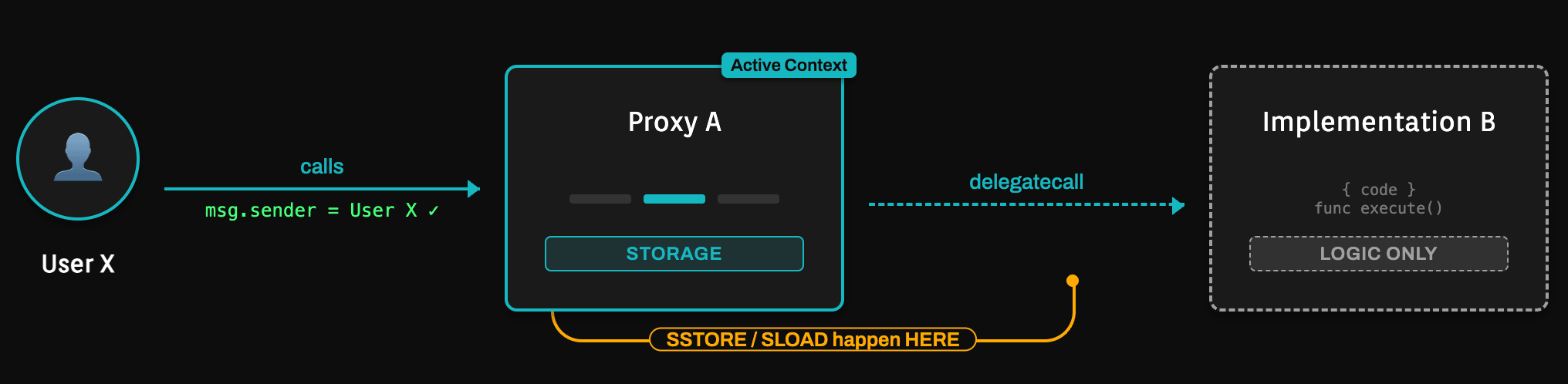

1.1 The DELEGATECALL mechanism and context preservation

The core of any proxy pattern is the

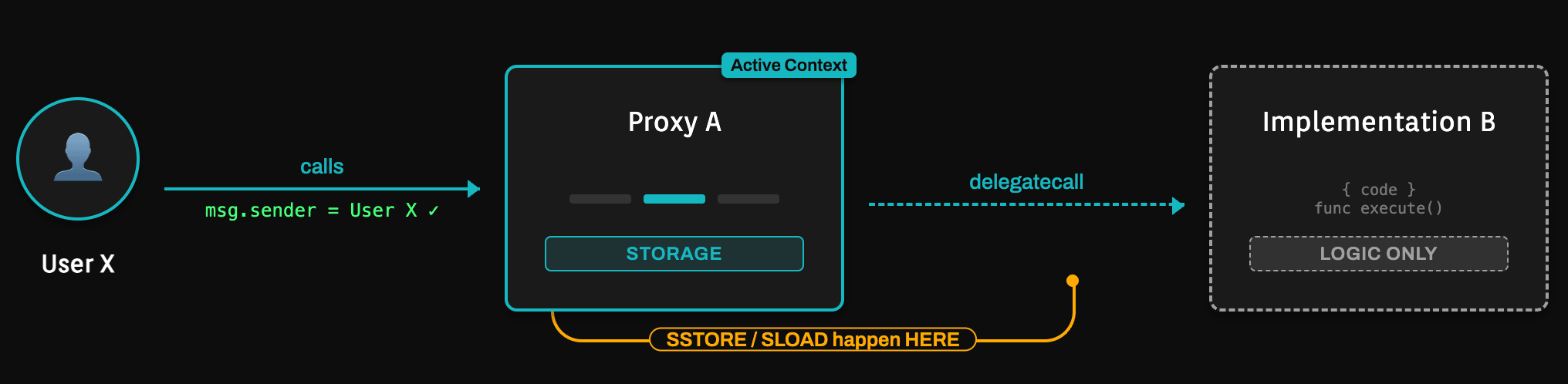

DELEGATECALL opcode (0xf4). Introduced in EIP-7, this opcode differs fundamentally from a standard CALL. While CALL executes the target contract's code in the target's own storage context, DELEGATECALL executes the target's code (the implementation) within the context of the calling contract (the proxy).Technical implications:

Storage persistence: When Proxy A executes a

DELEGATECALL to Implementation B, any SSTORE (write) or SLOAD (read) operations occur within Proxy A's storage. Implementation B acts as a pure logic library; its own storage remains uninitialized and often empty.Context preservation: The global variables

msg.sender, msg.value, and msg.data remain unchanged. If User X calls Proxy A, which delegates to B, the logic in B perceives msg.sender as User X, not Proxy A. This is critical for access control and business logic integrity.This architecture creates an "illusion of mutability." The contract address interacted with by the user (the Proxy) and its state (the data) remain constant. Evolution is achieved by altering a state variable within the Proxy that stores the implementation address, thereby redirecting the logic flow.

1.2 Storage layout and the risk of collision

The EVM manages persistent storage as a 32-byte word mapping. Solidity abstracts this by assigning "slots" sequentially to declared state variables.

- Slot 0: First declared variable.

- Slot 1: Second declared variable (subject to packing).

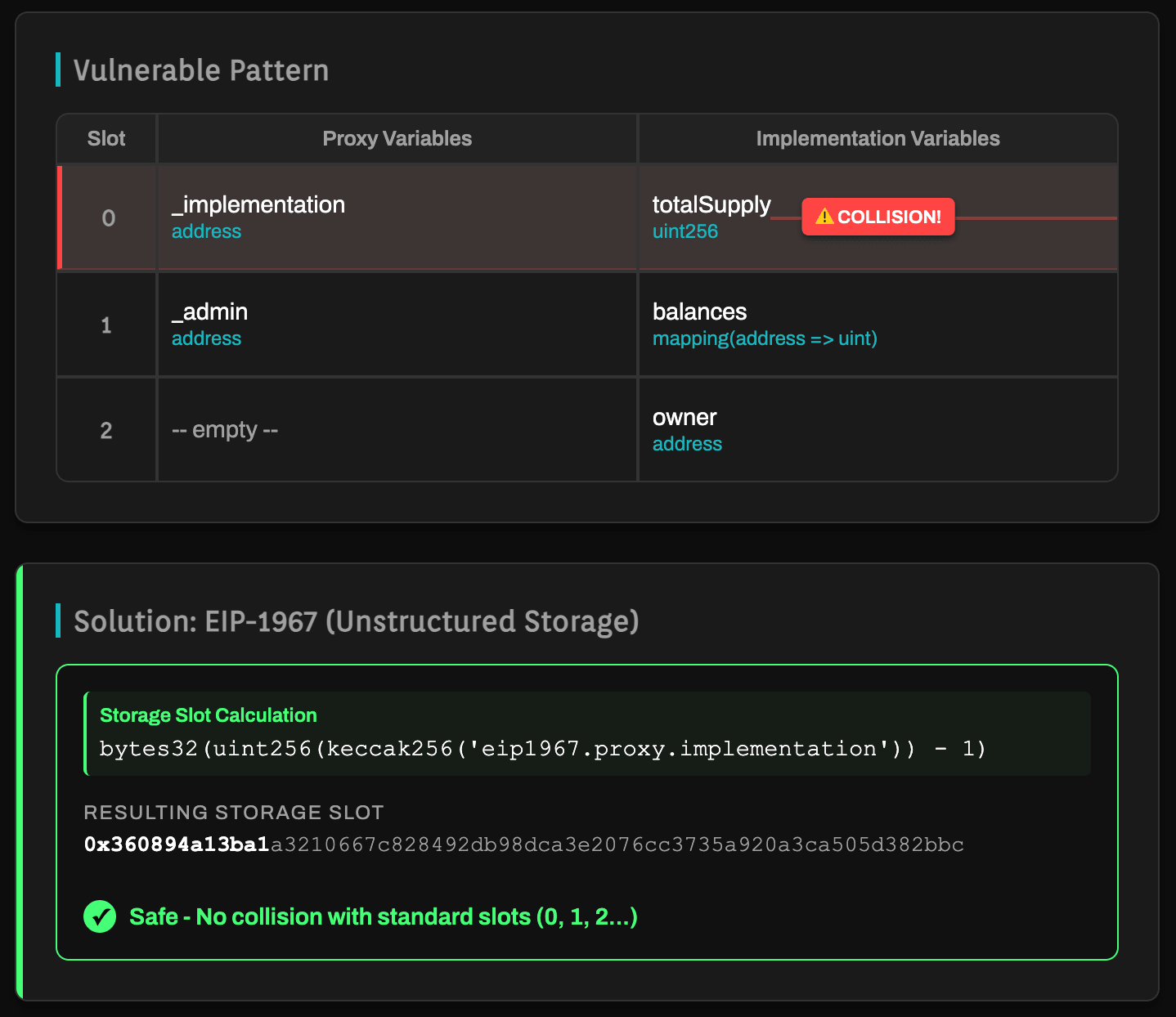

The storage collision vulnerability:

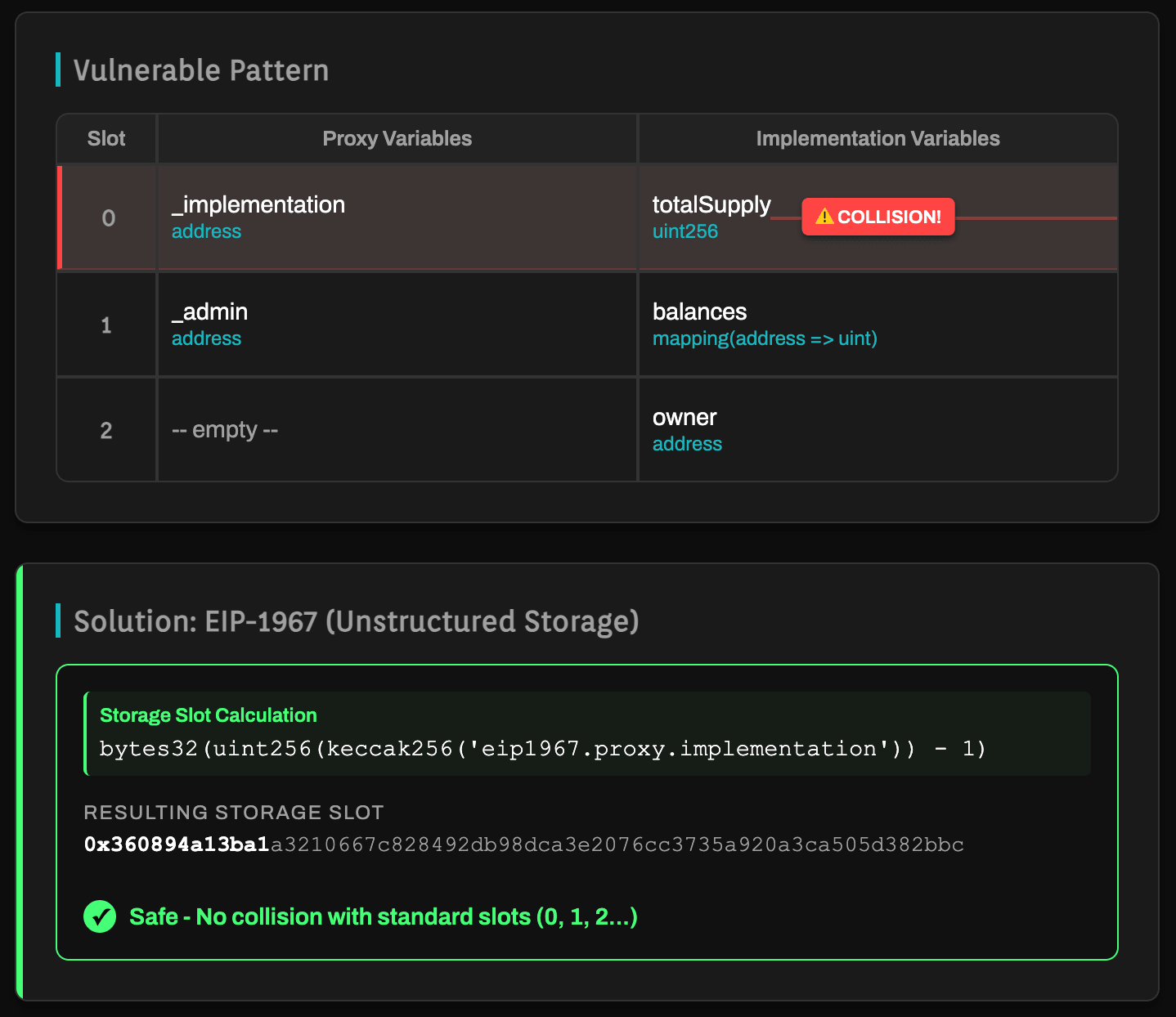

Because the Proxy and Implementation share the same storage address space, they must maintain strict alignment on the layout. If the Proxy utilizes Slot 0 for the

address implementation, and the Implementation utilizes Slot 0 for a uint256 totalSupply, a catastrophic collision occurs. An update to the logic's totalSupply will overwrite the Proxy's implementation address, potentially bricking the contract or redirecting execution to an arbitrary address.Mitigation: Unstructured storage (EIP-1967)

To prevent administrative variables in the Proxy from colliding with logic variables, modern standards utilize "Unstructured Storage." Instead of sequential slots, administrative variables (e.g.,

_implementation, _owner) are stored in pseudo-random slots derived from constant hashes.EIP-1967 logic: The implementation slot is defined as

bytes32(uint256(keccak256('eip1967.proxy.implementation')) - 1). The probability of a standard Solidity variable colliding with this specific slot is cryptographically negligible.

2. Deep dive analysis of upgradeability patterns

By 2026, the ecosystem has converged on four primary patterns, each with distinct gas profiles and attack surfaces. Understanding these patterns is essential for both protocol development and security audits.

2.1 Transparent proxy pattern (TPP)

Historically the industry standard, TPP was designed to mitigate function selector clashing.

- Mechanism: TPP implements a conditional routing logic based on

msg.sender.- If

msg.sender == Admin: The Proxy executes administrative functions (e.g.,upgradeTo). Logic calls are reverted. - If

msg.sender != Admin: The Proxy delegates calls to the implementation. The Admin cannot interact with business logic.

- If

- Performance overhead: In 2026, TPP has seen a decline due to gas inefficiency. Every transaction requires an

SLOADof the admin address to perform the check, incurring a ~2,100 gas penalty (cold load) per transaction.

2.2 Universal upgradeable proxy standard (UUPS)

UUPS (EIP-1822) has emerged as the dominant pattern, driven by the need for high efficiency in L2 Rollups.

- Inversion of control: Unlike TPP, the upgrade logic resides in the Implementation, not the Proxy.

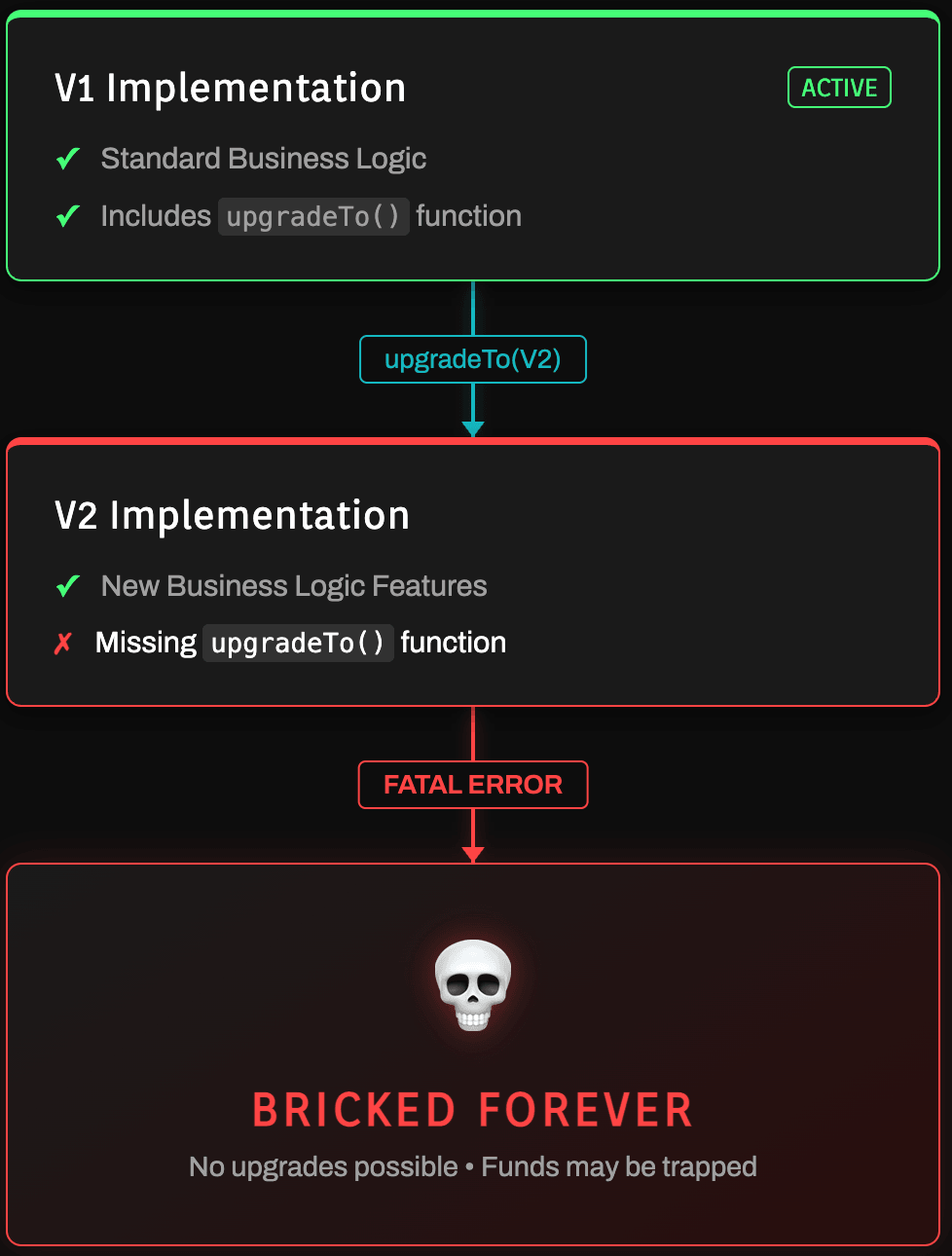

- Technical scenario: The implementation must inherit

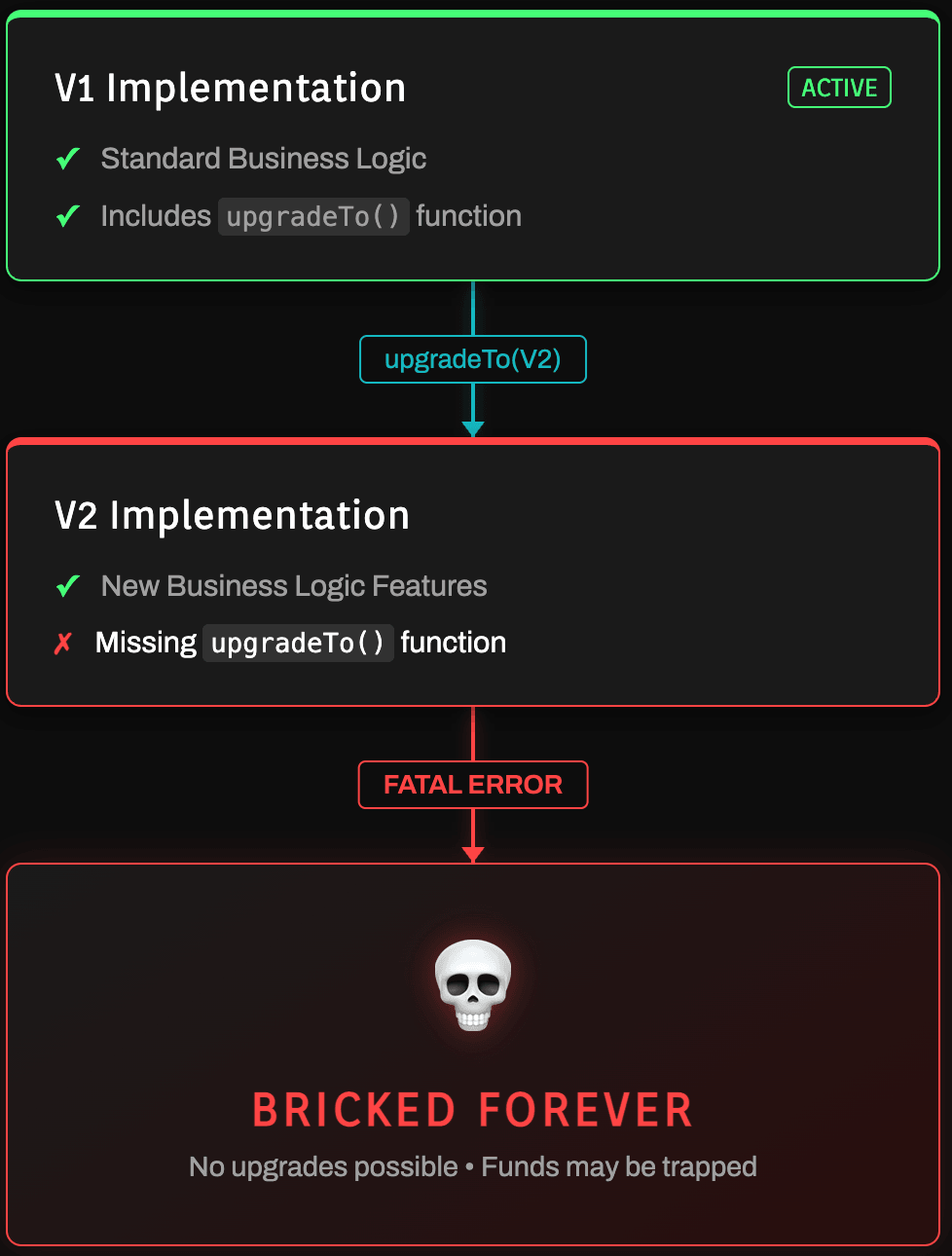

UUPSUpgradeable, which includes theupgradeTofunction. This function is executed viaDELEGATECALL, allowing the Proxy to update its own implementation slot. - The "silent death" risk: If an upgrade is deployed to a logic contract that lacks the

upgradeTofunction, the Proxy becomes permanently immutable. Funds can be trapped if the new logic is flawed, as the mechanism to perform a subsequent upgrade is lost.

2.3 Beacon proxy pattern

Designed for massive scalability (e.g., smart wallets, fractionalized NFTs), allowing thousands of proxies to be upgraded in a single atomic transaction.

- Architectural indirection: Proxies do not store the implementation address. Instead, they store the address of a Beacon contract.

- Workflow: Proxy → Call Beacon → Fetch Implementation Address →

DELEGATECALLto Logic. - Systemic risk: The Beacon represents a massive single point of failure. A compromised Beacon or a malicious upgrade simultaneously affects every user in the ecosystem.

2.4 Diamond standard (EIP-2535)

The Diamond Standard, or "Multi-Facet Proxy," addresses the 24KB

Spurious Dragon bytecode limit and organizes complex systems. For a practical example of auditing Diamond contracts, see our competitive audit case study.- The facet model: A Diamond Proxy delegates to multiple implementation contracts (Facets) based on function selectors.

- Diamond storage: Utilizes namespaced structs stored at unique hashes (e.g.,

keccak256("com.protocol.facetA")). This prevents cross-facet storage corruption. - Audit complexity: While powerful, Diamonds are notoriously difficult to audit. Tracking execution flow across multiple facets requires specialized tooling to ensure

diamondCuthasn't introduced backdoors.

3. 2025 academic insights: Tools and taxonomies

Academic research in 2025 has shifted the perception of upgrades from "useful features" to "critical threat vectors."

3.1 "The dark side of upgrades": Risk taxonomy

The study analyzed 37 major incidents and identified over 31,000 issues in active contracts.

Table 1: Taxonomy of upgrade risks

| Category | Specific risk | Description & impact | Awareness level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initialization | Proxy uninitialized | Deployment occurs but initialize() is not called atomically. Attackers front-run to gain ownership. | High |

| Storage | Storage collision | V2 layout conflicts with V1 or Proxy variables, corrupting critical state. | Critical |

| Logic | Upgrade bricking | V2 (UUPS) lacks upgradeTo function, rendering the system immutable. | Medium |

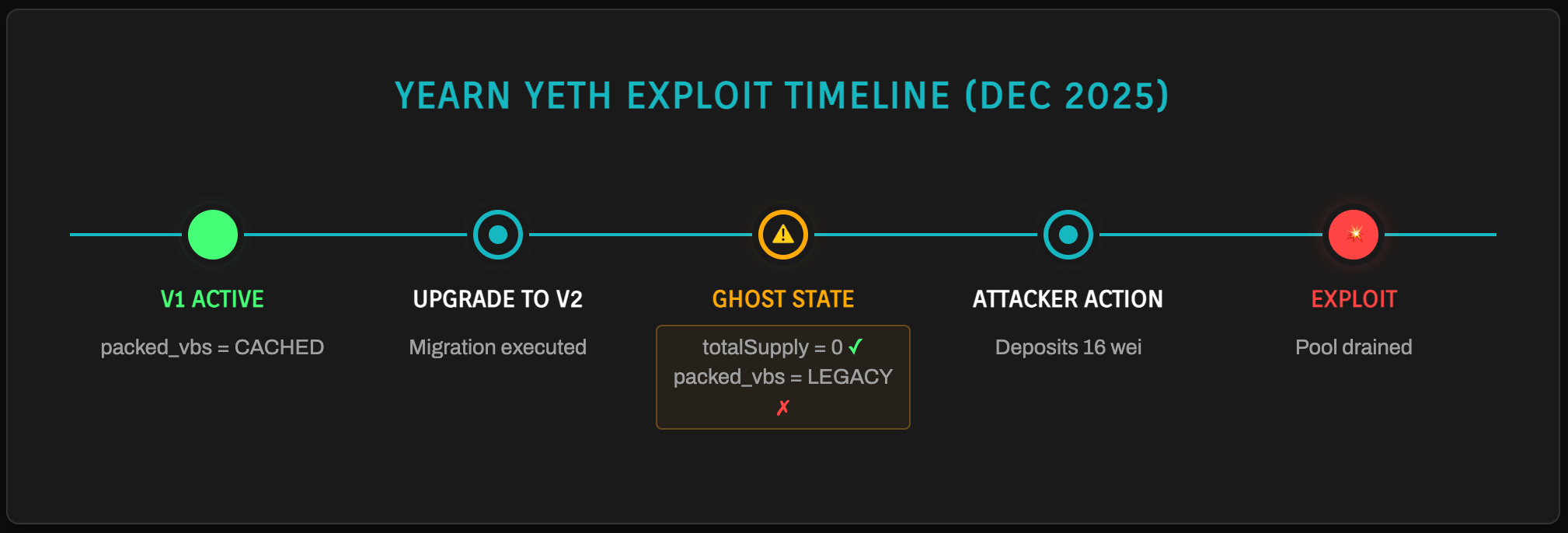

| Logic | Ghost state | V2 fails to sanitize or migrate legacy state from V1 (e.g., Yearn 2025 exploit). | Critical |

| Access | Malicious logic | Admin upgrades to a "drainer" contract (Rug Pull). | High |

3.2 PROXION and CRUSH analysis

- PROXION: Using EVM emulation and bytecode disassembly, PROXION revealed that 54.2% of Ethereum contracts are proxies, many with unverified "Hidden Contracts" as logic.

- CRUSH: Utilizes symbolic execution to detect Type Collisions. It identified over $6M in vulnerabilities where a V2 implementation interpreted Slot 0 (an address) as a

uint256, leading to logic failure.

4. Security vectors and failure modes: Post-mortem analysis

4.1 Initialization front-running

In UUPS and TPP, implementation contracts cannot use constructors for state initialization (as they run in the logic context, not the proxy context). They use

initialize() functions. If the initialize() call is not performed atomically with the proxy deployment (via ERC1967Proxy with calldata), an attacker can front-run the transaction, set themselves as the owner, and self-destruct the implementation or drain the proxy.This attack vector is closely related to the MEV and front-running vulnerabilities we've covered in previous articles.

4.2 Function selector clashing

Functions are identified by the first 4 bytes of their Keccak-256 hash.

transfer(address,uint256)->0xa9059cbb

An attacker can brute-force a function signature that matches an administrative selector (e.g.,

upgradeTo(address)). If a logic contract contains this colliding signature, a user might inadvertently trigger an upgrade when calling what appears to be a standard business function.5. 2025 case study: Yearn Finance yETH exploit (Dec 2025)

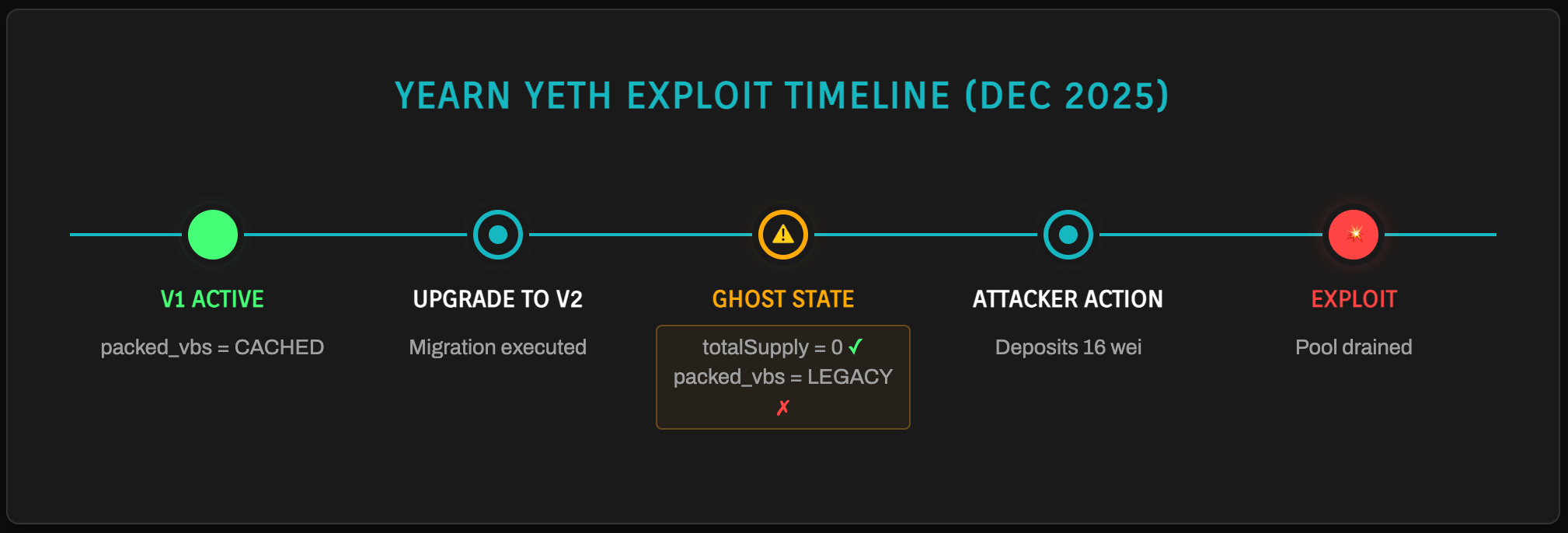

The vector: Ghost state corruption.

The yETH pool underwent a logic upgrade. The V1 logic utilized cached virtual balances (

packed_vbs) to optimize gas.- During the upgrade to V2, the

totalSupplywas reset due to a migration bug. - However, the

packed_vbsin the Proxy storage were not cleared. - The attacker deposited a negligible amount (16 wei).

- The V2 logic, seeing

totalSupply == 0, triggered a "first deposit" routine but calculated shares using the "Ghost State" (the massive legacypacked_vbs). - The attacker was minted an astronomical amount of tokens, draining the pool.

This exploit highlights why fuzz testing and formal verification are essential for upgrade scenarios, edge cases like "first deposit after upgrade" are precisely where mathematical invariants break down.

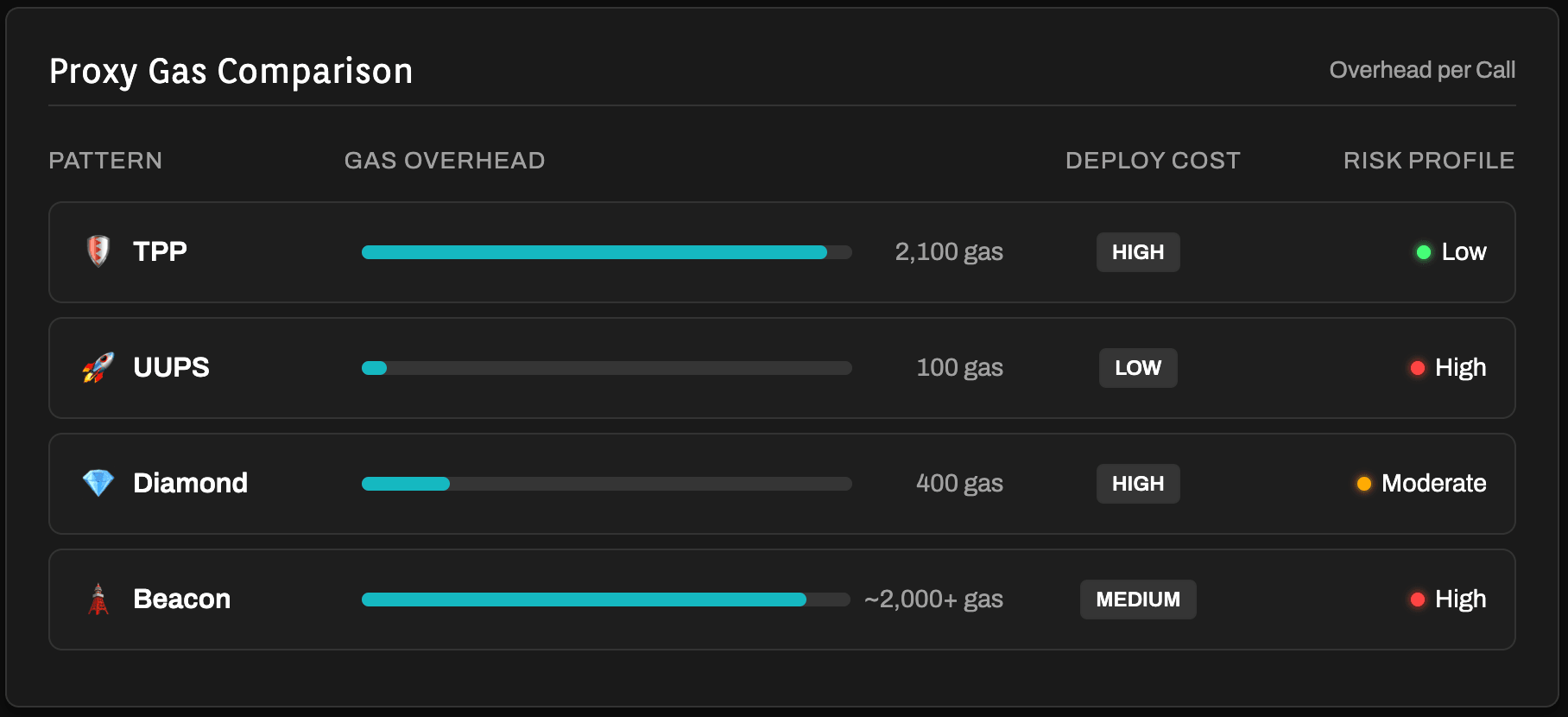

6. Gas benchmarks and economic efficiency (2026 data)

Understanding the gas overhead of each pattern is critical for audit cost planning, more complex patterns require deeper review and higher security budgets.

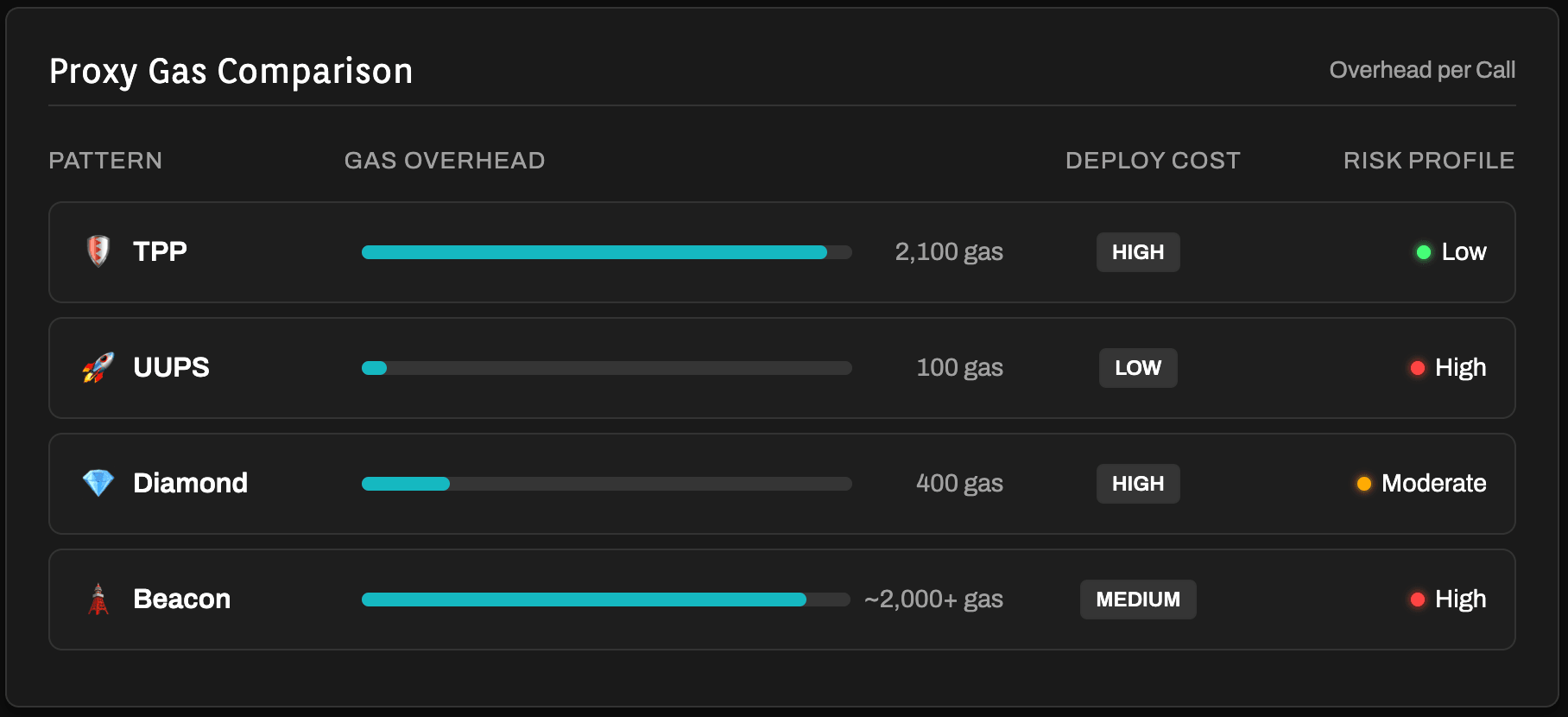

Table 2: Comparative execution analysis

| Pattern | Execution overhead | Deployment cost | Risk profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transparent (TPP) | High (~2,100 gas) | High (3 contracts) | Low (Mature) |

| UUPS | Minimal (~100 gas) | Low (2 contracts) | High (Bricking risk) |

| Diamond | Moderate (~400 gas) | High (Facet-based) | Moderate (Complexity) |

| Beacon | High (Internal Call) | Moderate | High (Single Point of Failure) |

7. Mitigation strategies and the future of upgradeability

7.1 EIP-7201: Namespaced storage layouts

To eliminate collision risks, EIP-7201 formalizes namespaced storage. Using Solidity annotations, developers can define safe storage locations:

1/// @custom:storage-location erc7201:protocol.main2struct MainStorage {3 uint256 balance;4}

This ensures the compiler calculates slots based on a unique hash, removing the danger of sequential displacement.

7.2 AI-assisted delta auditing

By 2026, standard practice involves AI-driven audit processes that compare the bytecode of V1 and V2 to detect storage slot shifts and invariant violations before the

upgradeTo transaction is signed.8. Conclusion

The upgradeability landscape of 2026 is defined by a tension between operational flexibility and security integrity. While UUPS has won the efficiency battle, it has introduced a "bricking" fragility that requires rigorous deployment discipline. The era of "naive upgrades" has ended; security researchers must now view upgradeable contracts not as static code, but as dynamic state-management systems where the legacy of the past (storage) can fundamentally compromise the logic of the future. The transition to verifiable state management is the only path toward protocol ossification and long-term security.

Get in touch

Auditing upgradeable contracts requires specialized expertise that goes beyond standard smart contract security. At Zealynx, we've identified storage collision risks in protocols governing over $50M in TVL, vulnerabilities that automated tools consistently miss.

Whether you're choosing between UUPS and Transparent Proxy for a new deployment, planning a complex migration, or need a comprehensive audit of an existing upgradeable system, our team combines deep EVM expertise with systematic methodology.

What we offer:

- Proxy pattern selection consulting — Choose the right architecture for your use case

- Storage layout verification — Detect collision risks before deployment

- Upgrade migration audits — Ensure V1 → V2 transitions don't introduce ghost state

- Delta audits — Specialized review of changes between versions

FAQ: Smart contract proxy patterns and upgradeability security

1. What is a smart contract proxy pattern and why do protocols use them?

A smart contract proxy pattern is an architectural design that separates a contract's storage (where data lives) from its logic (the code that processes transactions). Users interact with a "proxy" contract that holds all the state, while the actual business logic lives in a separate "implementation" contract. When called, the proxy uses

delegatecall to execute the implementation's code while keeping data in the proxy's storage.Protocols use proxy patterns because smart contracts on Ethereum are immutable by default, once deployed, the code cannot be changed. This creates problems when bugs are discovered, features need updating, or gas optimizations become available. Proxy patterns solve this by allowing teams to deploy new implementation contracts and simply update the proxy's pointer, effectively "upgrading" the contract without changing its address or losing user funds. For protocols managing significant Total Value Locked (TVL), this flexibility is essential for long-term maintenance.

2. How much does it cost to audit an upgradeable smart contract in 2026?

Auditing upgradeable contracts costs 20-40% more than auditing equivalent non-upgradeable contracts due to the additional complexity. Based on 2026 audit pricing benchmarks:

- Simple upgradeable token (UUPS): 20,000

- Standard DeFi protocol with proxy: 130,000

- Diamond Standard (EIP-2535) protocols: 200,000+

- Upgrade migration audit (V1 → V2): Additional 40,000

The premium exists because auditors must verify: storage layout compatibility across versions, proper initialization guards, upgrade authorization controls, and potential ghost state issues. Diamond contracts are the most expensive due to their multi-facet complexity requiring specialized tooling to track cross-facet dependencies.

3. What is the difference between UUPS, Transparent Proxy, Beacon, and Diamond patterns?

Each proxy pattern has distinct trade-offs:

Transparent Proxy (TPP): The upgrade logic lives in the proxy itself. It routes calls based on

msg.sender admins access upgrade functions, regular users access business logic. Pros: Battle-tested, clear separation. Cons: ~2,100 gas overhead per transaction for the admin check.UUPS (EIP-1822): The upgrade logic lives in the implementation contract, not the proxy. Pros: Minimal gas overhead (~100 gas), smaller proxy bytecode. Cons: If you deploy an implementation without the upgrade function, the contract is permanently bricked.

Beacon Proxy: Multiple proxies point to a single "Beacon" contract that stores the implementation address. Upgrading the Beacon simultaneously upgrades all proxies. Pros: Efficient for deploying thousands of identical contracts (smart wallets, NFT collections). Cons: Single point of failure, a compromised Beacon affects every user.

Diamond Standard (EIP-2535): One proxy delegates to multiple implementation contracts ("Facets") based on function selectors. Pros: Overcomes 24KB bytecode limit, granular upgrades. Cons: Highest audit complexity and cost, requires specialized tooling.

4. What is a storage collision vulnerability and how can it drain my protocol?

A storage collision occurs when the proxy and implementation contracts use the same storage slot for different variables. Since

delegatecall executes implementation code using the proxy's storage space, misaligned variables can corrupt critical state.Example attack scenario:

1// Proxy stores implementation address in Slot 02contract Proxy {3 address implementation; // Slot 04}56// Implementation uses Slot 0 for totalSupply7contract Implementation {8 uint256 totalSupply; // Slot 0 - COLLISION!9}

If an attacker calls a function that sets

totalSupply = 0xAttackerAddress, they've actually overwritten the proxy's implementation pointer. The next transaction now delegates to the attacker's malicious contract, which can drain all funds. The CRUSH tool identified $6M+ in vulnerabilities from this exact pattern.Prevention: Use EIP-1967 unstructured storage (stores admin variables at pseudo-random hash-based slots) or EIP-7201 namespaced storage layouts.

5. What is "upgrade bricking" and how do I prevent my UUPS contract from becoming stuck?

Upgrade bricking is a catastrophic failure mode specific to UUPS proxies where the contract becomes permanently immutable because the upgrade mechanism itself is lost.

How it happens: In UUPS, the

upgradeTo() function lives in the implementation contract (not the proxy). If you upgrade to a new implementation that forgot to include this function, or if the function has a bug that always reverts, you can never upgrade again. Any bugs in the new logic cannot be fixed, potentially trapping user funds forever.Prevention strategies:

- Automated checks: Use deployment scripts that verify the new implementation contains a functional

upgradeTo()before executing - Timelocks: Add a delay between upgrade announcement and execution, allowing security review

- Multisig requirements: Require multiple signatures for upgrades to prevent single-point-of-failure decisions

- Upgrade simulation: Test the upgrade on a fork before mainnet deployment

- Formal verification: Mathematically prove that critical invariants (including upgradeability) are preserved

6. What is "ghost state" and how did it cause the Yearn 2025 exploit?

Ghost state refers to legacy data left in proxy storage after an upgrade that the new implementation logic doesn't expect or properly handle. While the new code may reset or ignore certain variables, other state from V1 remains "haunting" the storage, potentially causing calculation errors.

The Yearn yETH exploit (Dec 2025):

- V1 logic stored cached virtual balances (

packed_vbs) to optimize gas - During the V2 upgrade,

totalSupplywas reset to 0, butpacked_vbswas not cleared - An attacker deposited 16 wei into the pool

- V2 logic saw

totalSupply == 0, triggering "first deposit" calculations - However, share calculations used the ghost state (

packed_vbscontaining massive values from V1) - The attacker was minted an astronomical number of tokens, draining the entire pool

Prevention: During upgrade audits, map every storage slot used by V1 and verify V2 either: (a) uses it compatibly, (b) explicitly resets it, or (c) has logic that handles unexpected values. Fuzz testing upgrade scenarios is essential.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Delegatecall | EVM opcode executing another contract's code in the calling contract's storage context, enabling proxy patterns. |

| Proxy Pattern | Smart contract design separating storage and logic, enabling upgrades by changing implementation address. |

| Storage Slot | 32-byte memory location in EVM persistent storage where contract state variables are stored. |

| Diamond Standard | Multi-facet proxy pattern (EIP-2535) routing function calls to multiple implementation contracts. |

| Storage Collision | Critical vulnerability where proxy and implementation use the same storage slot for different variables. |